Exploring backoff

Back off is the amount of time to wait before retrying a failed action. There are many choices for how to back off, including constant backoff (wait 10 seconds, then try again), random backoff (wait x seconds, where x is a random variable with some distribution), exponential backoff (wait exponentially longer each time you retry) and exponential random backoff (randomly select from a distrubtion that gets exponentially longer each time you retry)

What we are trying to model:

Clients send requests to a service that does some processing and sends a response. The service can olny process so many requests at a itme and all additional requests will be told to retry. If the service is overwhelmed it will only be able to respond to a subset of totla requests that are being processed or need to be rejected. We are interested in what retry strategy yields the best latency for clients and the least load for servers.

The model:

Our model will rely on simulating the service and clients in a single proccess. Our simulation will operate with discrete time steps, during which clients my send a request and the service may make incremental progress on requests and send responses.

We will model the service as a queue with a fixed size. If the queue is not full when a request arrives it is put on the queue and removed some time steps later to representing processing. We will model the time spent in the queue as constant as long as the service is not overwhelmed. If the queue is full, then the client is sent a service unavailable response after some number of ticks and is expected to retry the request. If the service has a very large number of outstanding requests that need responses, either successful or failed, it is considered overwhelmed and will only process a subset of them. While overwhelmed, the service will only proecss a subset of requests, with each request equally likely to make forward progress. This means that if there are many more failed requests, each successful request is unlikely to make progress.

We will generate many clients and model when they send their first request as a uniformly random distribution with a large spike in requests near the beginning of the experiment.

Below is a figure showing an example of when clients made their first request. On the x-axis is time steps and the y-axis is the number of requests.

Experimental setup

The experiment is set up such that we run for 3000 time steps, the first 1000 time steps the clients send requests and the remaining 2000 time steps allow the service to finish processing requests. The service may process 5 requests at a time and each request takes 5 time steps (as long as the service is not overwhelmed). 800 clients are created, and 20% of them contribute to the initial spike, the remaining 80% have their first request uniformly randomly spread throughout the first 1000 time steps. If the service is already processing 5 requests when another arrives, it will wait 1 time step before informing the client that the request has failed and it must try again. The service is considered overwhelmed when it is processing more than 25 requests. These numbers were selected such that the service will be drastically overwhelmed in order to see how it returns to a steady state. The numbers were kept low to make it slightly easier to reason about. Similar results are seen when scaling the numbers.

We consider the following backoff strategies:

- No backoff (NB), retry immediately

- Constant backoff (CB), retry after 5 ticks

- Uniformly random backoff (URB), retry after x ticks where x ~ U(0,5)

- Exponential backoff (EB), retry after max(2^attempts, 30)

- Random Exponential backoff (REB), retry after x ticks where x ~ U(0, max(2^attempts, 30))

Results

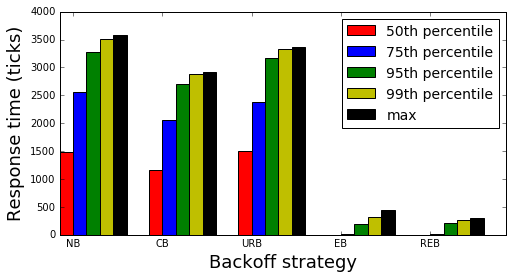

Below is a figure summarizing the results of the experiment:

Both exponential backoff and random exponential backoff yield significantly better response times than the other three strategies. The inituition for this is that as the initial requests fail, both EB and REB will back off much more heavily than the other strategies which better spreads out the burst in requests and gives the service time to recover. Interestingly, exponential backoff has slightly better 75th response times than random exponential backoff, however, the long tail is better under REB.

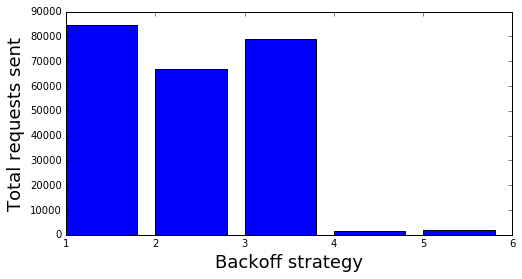

Next we look at the total number of requests sent by each of the back off strategies.

Again, we see that EB and REB send significantly fewer requests than the other backoff strategies. The intuition is roughly the same as before. Interestingly, EB sends fewer requests then REB, but not significantly so.

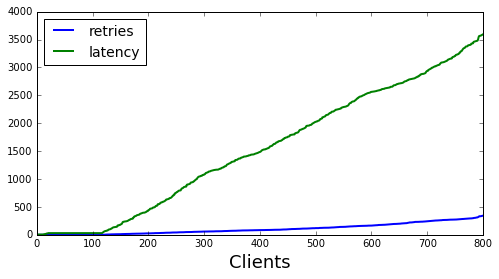

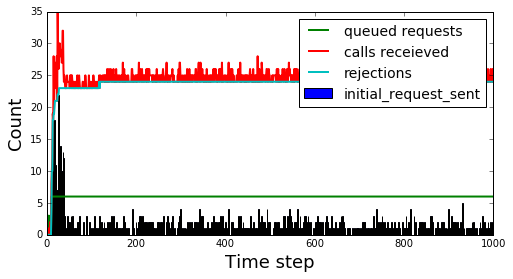

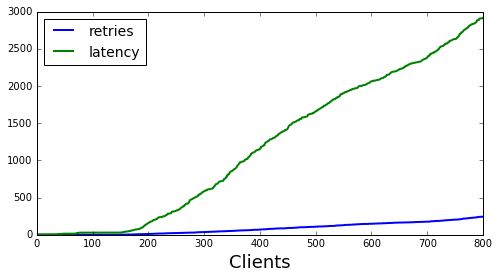

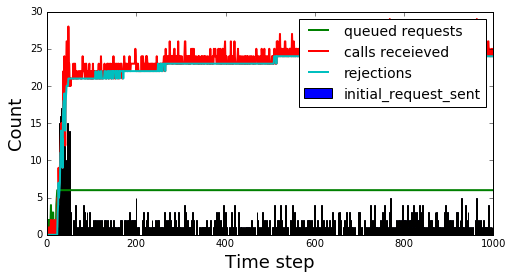

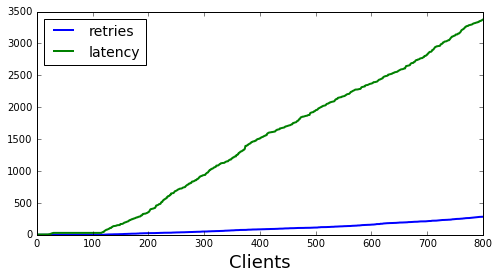

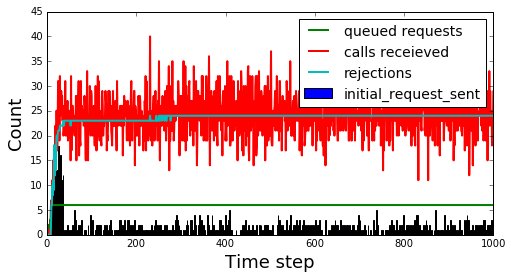

Next, we will look more closely at the behavior of each backoff strategy. For each strategy we will look at two figures, the first shows the number of requests made and the latency observed by each client (sorted by latency observed). This figure gives a view of the experience for each user. The second figure shows a view from the server side at each time step. It shows the requests queued, the requests received, the requests rejected and how many clients sent their initial request for each time step.

First we will look at the no backoff case. As might be expected, immediately after the hotspot hits the service is overwhelmed consistently as all the clients that were part of the hotspot continue to hammer the server.

Next we look at the constant backoff case. It looks fairly simiarly to the no backoff case, however, if you look carefully you will notice that there slightly less seasonality in the requests received at each time step. This is because patterns will now be spread between 5 “buckets” instead of just 1 in the case of no back off.

Below is the uniform random backoff case. There is a lot more variation in the calls received compared to the previous to. I expect this is due to random hotspots cropping up due to uniformly sampling (see the Balls in Bins problem for more details) but haven’t investigated further.

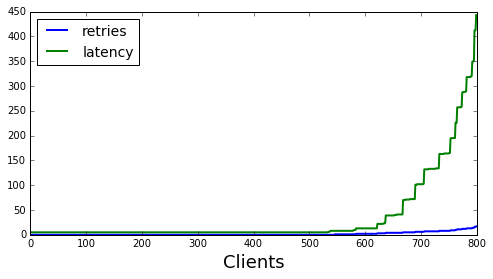

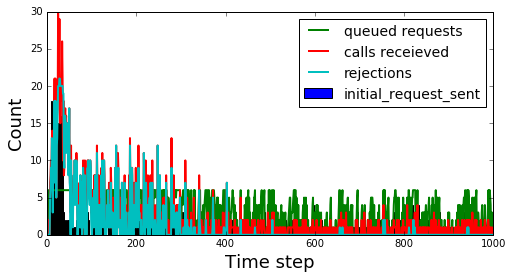

Next is exponential backoff case. Here we see the system responding much better to large burst. The interesting aspect here is that requests become seasonal following the initial hotspot and look like aftershocks following an earthquake. This can be very dangerous to a system’s health if the each “aftershock” further stresses the servers. In our model it isn’t particularly dangerous.

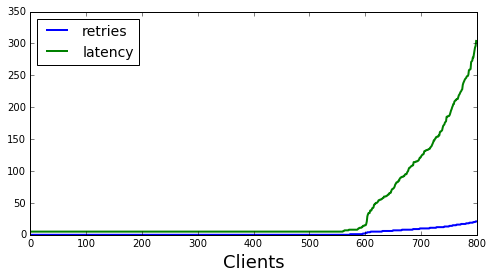

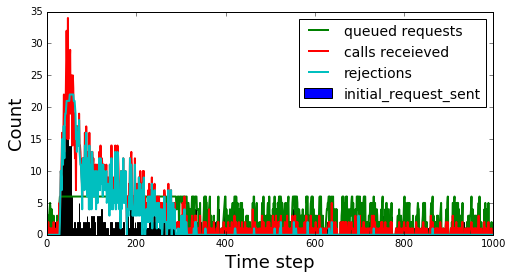

Finally there is random exponential back off. This looks quite similar to the exponential backoff case but there is no longer the seasonal component.

Issues with the model and additional experiments to try

It is important to note that this model is simply that, a model. Your mileage may vary the futher this model and your environment differ. Some aspects of the model to specifically call out are:

- Request time is a constant. In real systems request times vary for many reasons including what is requested. A more complete model may find that a user should backoff differently depending on the size of requests for example.

- Reject time is a (small) constant. In a real system the time to reject a request may vary and may not even reach the service.

- Overwhelmed servers largely spend their time rejecting requests. In real systems, this behavior is likely more complex and can be more catastophic (the server falls over).

In this experiment we only looked at a service that receives an extreme burst of requests. Additional experiments might consider looking at different arrival patterns, different back off strategies, and the tuning of backoff strategies.

Conclusion

Given our model above, we have found that random exponential backoff is the best strategy to choose. The model includes a large burst in requests which is an event most services can expect and be prepared for.